Siberian Intervention - Book Review

- Jody Ferguson

- May 29, 2024

- 3 min read

In the 1990s I traveled to the city of Vladivostok in Russia’s Far East. While there I visited the Naval Cemetery, where many of the city’s famous citizens are buried. My Russian friend pointed out to me the grave of a lone American, and then recounted how he had been part of the American ‘invasion’ of the Russian Far East. I asked my friend to explain and upon hearing this story for the first time, I was amazed and puzzled.

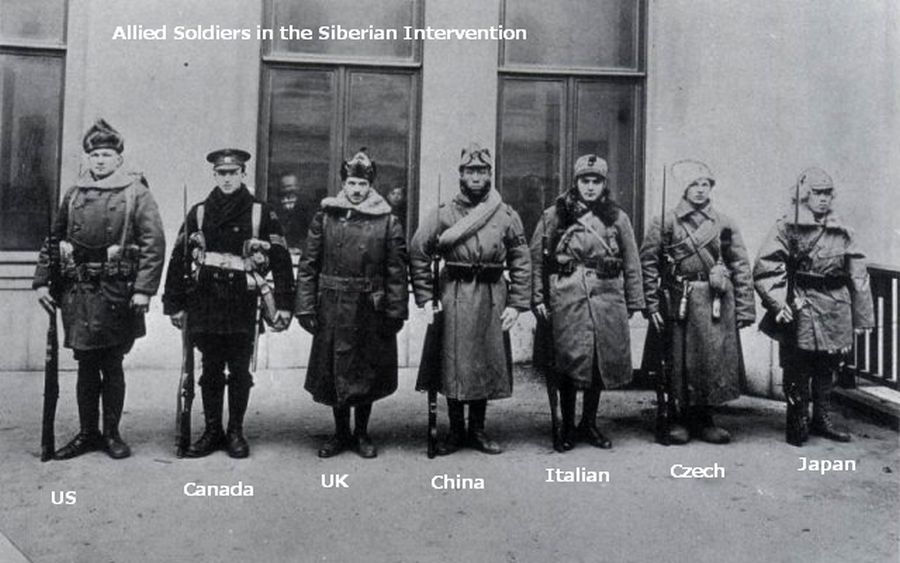

Upon returning home I did some reading (including the fine account by America’s most influential diplomat George Kennan, The Decision to Intervene), and I learned that in the closing days of the First World War President Woodrow Wilson reluctantly agreed to send several thousand U.S. soldiers to Russia’s Far North and Far East in a failed Allied multi-national campaign to ostensibly guard military supplies, a mission that increasingly became an effort to effect a certain outcome in the Russian Revolution favorable to the West. This forgotten episode of the First World War should be known and understood by all Americans, given the mutual distrust that has existed for more than a century between the United States and Russia.

Robert Willett’s book Russian Sideshow: America’s Undeclared War is a thorough examination of the Allied intervention in revolutionary Russia. His book starts with the painstaking decision by President Wilson to agree to support the British and French strategy to send Allied troops to the Murmansk/Archangelsk region in far northern Russia and to Vladivostok, Russia’s window on the Pacific Ocean, seven time zones away from Moscow. Initially the troops were meant to safeguard the massive stockpiles of military and humanitarian supplies that had been shipped to Tsarist Russia as it fought on the side of the Allies against the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary) in the First World War. But after the troops arrived in Russia, they suffered from what would become to be known as “mission creep.” The British leadership in northern Russia (all Allied troops were placed under the command of a British general) decided that Allied troops should link up with anti-Bolshevik forces and overthrow the new Soviet government under Lenin. The fighting in that area soon became brutal (more on this below).

In the Far East, General William Graves was extremely circumspect about using the more than 7,000 U.S. Army troops in anything other than a protective role. He refused to place them under the command of either the British or the Japanese leadership. Japanese forces made up the largest contingent of Allied soldiers in the Far East, and they took an active anti-Bolshevik posture, openly fighting Red Army forces while supporting the White anti-Bolshevik troops. They eventually lost more than five thousand dead in the campaign. Graves was able to keep U.S. troops mostly out of harm’s way, losing about 190 men, half to disease. Graves was also appalled at the atrocities carried out by Japanese troops and by both sides of the Russians fighting in the region. His zealous oversight saved many American and Russian civilian lives. The Allied withdrawal from the region was not until the summer of 1920, long after WWI had ended. Willett’s book includes the long, vague aide de memoire penned by Wilson in early 1918 about the U.S. decision to send forces to Russia. It is a well-written, informative book.

Whereas Willett’s book focuses on the big picture, James Carl Nelson’s work The Polar Bear Expedition is an account of the failed incursion around Arkhangelsk by the American Expeditionary Force, North Russia.

Nelson describes the brutal fighting and horrific conditions of a regiment of 3,000 U.S. Army soldiers sent to northern Russia as part of the larger intervention. Alongside British, Canadian, and French troops, U.S. Army soldiers, drawn largely from the Detroit area, would end up savagely combatting Bolshevik forces for six months after the armistice ending WWI had already been signed in France. Not knowing what they were fighting for, facing a shortage of supplies, living in temperatures sometimes as cold as minus fifty degrees, and outnumbered by an enemy at times as much as 20-1, the men who proudly wore the Polar Bear patch of the 339th Regiment acquitted themselves admirably but at the cost of 235 dead. At times Nelson’s book is difficult to follow with the overwhelming attention to detail, but it is a worthwhile read.

As both writers point out, like subsequent failed U.S. combat missions in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, the mission to Russia in 1918 lacked clearly defined objectives or goals. This is an issue that has often vexed U.S. foreign policy and in this particular case, it created an enmity among the Russians that exists even to this day.

Comments